LIHU‘E — It was said that during Kalakaua’s reign, literacy in Hawai‘i was the highest of any nation in the world. There were eight daily newspapers — two were printed in English and six in Hawaiian. Editor’s note: On Friday,

LIHU‘E — It was said that during Kalakaua’s reign, literacy in

Hawai‘i was the highest of any nation in the world.

There were eight daily newspapers — two were printed in English and

six in Hawaiian.

Editor’s note: On Friday, the Kaua‘i Museum celebrates its 50th anniversary. Museum leaders have chosen 50 stories from exhibits, collections and the archives of the museum to share with the public. One story will run daily through Dec. 3.

LIHU‘E — It was said that during Kalakaua’s reign, literacy in Hawai‘i was the highest of any nation in the world.

There were eight daily newspapers — two were printed in English and six in Hawaiian.

In 1820, the authors of this reading revolution arrived aboard the Brig Thaddeus along with an old printing press. Although the Hawaiian chiefs were ambivalent about the new Christian teachings, they did know the value of reading.

The traders that had been coming to Hawai’i, used the Hawaiians’ lack of literacy as a position of strength and to a man, kept this knowledge to themselves. The missionaries, on the other hand, wanted to teach everyone, from the highest to the lowest, to read. Of course reading the Bible was their primary goal.

As soon as the missionaries were sure of the orthography and pronunciation of an adequate number of words they prepared a primer or spelling book to be printed for the schools. Not only was this the first printing done in the Hawaiian Islands, but west of the Mississippi.

The chiefs in Honolulu were so excited by this endeavor that a few including Liholiho turned the press to knock off pages in their own language. Not too long after that, Liholiho tried to contain reading to only the chiefs, but it was too late, the magic pages were out and the schools started.

Kaua‘i responded more quickly to schooling than other islands, because of the ready cooperation of first Kaumuali‘i, then Gov. Kaikioewa.

In 1822, Kaahumanu made a trip to the leeward island with a retinue of some 800 people. “Many are the people – few are the books. I want elua alu (800) Hawaiian books to be sent hither.”

At the public examination of the students at Waimea on Jan. 7, 1829, the Rev. Peter Gulick wrote, “At the examination of 850 readers passed in review, they read of various parts of the books of which they studied and acquitted themselves very much to our satisfaction. One hundred and fifty-two men and forty-two women, most of them neatly dressed in European style, were also examined in the art of writing. They wrote on slates and manifested a very pleasing evidence of improvement.” After the examination some 5,000 people gathered at the governor’s house.

In a report for Kaua‘i in June 1831, the number of schools on the island was given at 200. The number of students was 9,000, and those able to read numbered 3,500. A large part of the population was going to school.

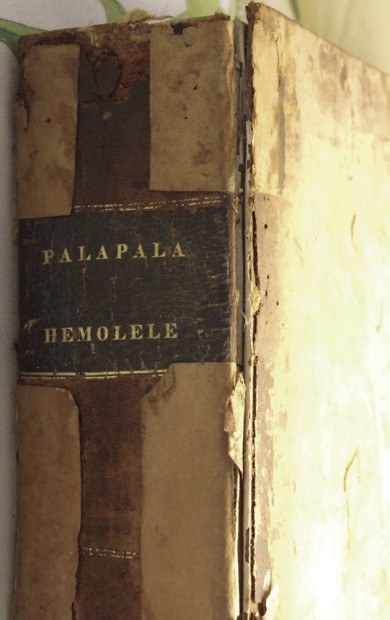

For the next decade, passages, scripture, hymns and more were published and then in 1839, the complete Bible was printed after another decade of work.

It was not without controversy. The conclave that met to standardize the language into a written form was not harmonious, to put it mildly, with loud disagreement over whether a “k” or a “t” should be used or whether “b” and “s” and other variations should be allowed. For many, reading the Bible was how one learned to read Hawaiian.