HANAPEPE HEIGHTS — Kaua’i resident Cynthia Kailikini “Cyndy” Blair had hoped her participation in the O’ahu-based, Self-Help Housing Corporation of Hawaii would help her reach a lifelong dream, that of owning her own home. Instead, her participation in a 12-unit

HANAPEPE HEIGHTS — Kaua’i resident Cynthia Kailikini “Cyndy” Blair had hoped her participation in the O’ahu-based, Self-Help Housing Corporation of Hawaii would help her reach a lifelong dream, that of owning her own home.

Instead, her participation in a 12-unit housing project overlooking Hanapepe Valley turned out to be nightmare.

After Blair voiced concerns about the laying of her house slab before the exact boundary lines were known, and other disagreements with leaders in the self-help program, she claims she was axed from the program in December 2003.

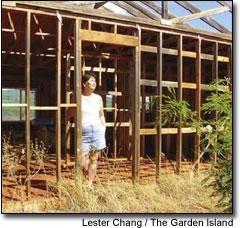

Today, only half of the home is completed, and the wooden frame has developed dry rot, having been exposed to the elements after work halted in March or April of 2003.

Blair’s salvation is that she secured a private loan this month to close out a $140,000 loan from leaders of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development Division for the house and property.

Blair, a single parent, owns the house and the land, but she has to get another loan to build the home, a major hurdle because she is already carrying another loan.

“What happened to me has been a nightmare,” she said. Blair said the challenges she encountered in trying to work with Claudia Shay, who heads the Self-Help Housing Corporation of Hawaii program, are not unique, and that other folks, perhaps not as vocal as she, have had similar problems.

Shay was not immediately available for comment on Friday.

Those in Shay’s organization have led the building of such homes on Kaua’i since the early-to-mid 1980s, when she introduced the concept to late former Kaua’i Mayor Tony T. Kunimura.

Shay founded the organization in response to a housing crisis, and has said her origination has built 500 homes in the state since 1984.

Members of many families are grateful because the program has enabled them to own homes they could not otherwise have afforded.

Blair chased after the same dream.

Blair is a 1973 graduate of Waimea High School, a Native Hawaiian and the daughter of Abraham and Ermine Kailikini of Hanapepe Valley, and has been employed by the Hyatt Corporation for 24 years. Over the last 14 years, she has been employed by the Hyatt Regency Kauai Resort & Spa and now the Grand Hyatt Kauai Resort and Spa in Po’ipu, currently as a night auditor.

Blair found out about Shay’s program through a newspaper in 2001. She signed up for the self-help housing program in 2002.

Her lot is the type which million-dollar homes are built on. Although the flag lot sits behind another lot, it offers a panoramic view of cane fields, valley and mountains. An updraft of wind would keep the house cool.

Blair secured a $140,000 USDA loan to build her home. Of that amount, $71,000 was used for the purchase of the lot, and $69,000 would be used to buy building materials. The funding amounts were based on Blair’s income.

Under the guidance of a foreman and with the help of Blair’s daughter and friends, including those from Honolulu, Blair began working on her house in June 2002.

Under the self-help housing scheme, neighbors help each other build their homes, saving money in exchange for their sweat equity. They are required to put in so many hours of work a week, on their home and the homes of others.

The home-builders used their own tools, or those that were collectively bought for the project.

As part for the program, Blair and others pledged to work 32 hours a week until the home was completed. As part of the project, Blair donated her time to help other families or individuals to finish their homes, and they did the same for her.

Families went from home to home to put them up. However, some families didn’t always show up for the work, as the program progressed, Blair said.

The house slab, or the home’s foundation, was put up before all the boundary pins were identified, Blair said.

Not all the pins were found, but the foundation was laid on Nov. 15, 2002, Blair said.

A survey done in January 2003 showed the folly in rushing ahead with the project, Blair said.

The survey essentially showed that one side of the house was built two feet closer to a neighbor’s property than was originally spelled out in the plot plan, Blair said. The result was this: The turnaround for vehicles on her lot was too small.

She said she wanted to move the garage more toward the ocean so that her vehicle turn-around area would be bigger. She met with resistance to that idea.

She contacted federal and state legislators about her problems, but was told that “there was nothing they could do,” she said.

Blair said she contacted Shay, who told her that the fixes Blair proposed for her home and lot were “doable.”

“After I complained, she put my house on hold, and no one was able to work on my property. That house was off-limits,” Blair said.

She said she and others had put in nine months of work before the work stopped, and she was “terminated “from the project in December 2003.

A shell of the home she had hoped to build is all that remains. Wall siding can be found on three quarters of the house, half of the roof is covered, sheeted ply board has been installed on one quarter of the home, and 10 windows are up.

She wanted the home to last, and paid an additional $200 to install Tyvek paper, which provides additional protection between the wall and the siding, to prevent water damage.

In all, Blair said she put in 2,200 hours of sweat equity in the building of the 1,248-square-foot house with four bedrooms and two baths.

Those who built the other homes had a special interest in seeing the completion of Blair’s home.

“People moved into their homes on the 10th and 11th of September 2004,” Blair said. “All the houses (including Blair’s home) had to be completed before people could move in. Claudia waived that condition because my house sat idle.”

Blair said she had given thought about filing a lawsuit against Shay and others in her organization, but figures the money spent on legal fees could be used to fix up her new home.

She and officials with the USDA worked out an agreement that would allow her to secure a private loan of $86,820 to close out the original loan, including funds set aside for buying materials that were not used.

She currently pays nearly 7 percent interest on the private loan she has gotten, and voiced frustration that USDA officials didn’t monitor the work on her home, and didn’t intercede after she was terminated from the project.

The lack of monitoring by government agencies led her down the path to near ruin, she said.

Jack Mahan, the housing program director for the USDA program on the Big Island, said those in his division have no authority to intercede.

“In reality, we had no authority to step in the case,” he told The Garden Island. “So we tried to allow the parties to solve their differences. That is normally the way it works, and that took much longer than it should have.” He said that “there was a point at which we decided to do what we could do. We modified the loan, and reduced it to a point where she could pay it off.”

He said that, in reality, with USDA officials modifying the loan, Blair is “still getting a buy,” although not at a price she wants.

“The house prices have tripled (up there),” he said.

Blair said she feels lucky that she was able to work out that loan, allowing her to become owner of the home and land.

“People have told me to sell,” she said. But she won’t because the home is her future, an expensive one, she acknowledges.

“It is going to cost (her another, private) $90,000 loan, (totally perhaps) $260,000 to move into my home,” Blair said.

She remains undaunted. “I am keeping my fingers crossed, crossing my fingers and moving onto the next step,” she said. “I am taking whatever help I can get.”