LIHUÔE Ñ During times of natural disasters, cell phones that everyone takes for granted might not work. Where would that put people in terms of communication? Anyone who lived through Hurricane ÔIwa in November 1982, or Hurricane ÔIniki in September

LIHUÔE Ñ During times of natural disasters, cell phones that everyone takes for granted might not work.

Where would that put people in terms of communication?

Anyone who lived through Hurricane ÔIwa in November 1982, or Hurricane ÔIniki in September of 1992, likely recalls the frustration of not being able to call anyone on the phone, or receive calls from frantic friends and relatives on the other islands, Mainland or elsewhere, worrying about the safety of their loved ones on KauaÔi.

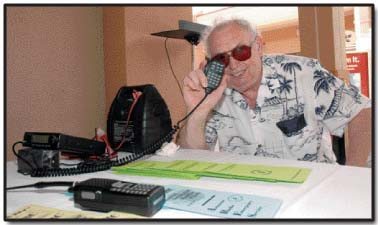

Ben Bohach and Jane Goldsmith of the Kauai Amateur Radio Club were on hand at a recent emergency-preparedness event, to provide some communications answers.

Bohach, a resident of Princeville, said heÕs been around Òoff and on for the past 10 years, but all the time for four yearsÓ as a member of the radio club.

During that time, there have been technological advancements in the field, with little change in the basic need to communicate.

As a demonstration of the technological advances, Bohach showed off a complete receiving and transmission unit that is powered by a self-contained energy source that takes up less space than a personal computer.

There have been over 100,000 messages of welfare and need sent via amateur radio since Hurricane Katrina wrecked havoc in Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, Bohach said. And the number keeps growing.

Because of their non-reliance on electricity, Bohach said the radios are always ready to go. His personal home setup involves three generators, five solar panels, and two deep-discharge batteries as power sources, so his ability to communicate is not impaired by a lack of standard electric power.

Using radio waves, there are units that can broadcast above and beyond the normal transmission levels, and linking with a worldwide network of radio users, messages from disaster-stricken areas are sent and delivered through similar radio organizations.

When disaster strikes and electricity is cut off, Bohach said radio might be the only form of communication available because, despite some cellular phones having the capability to make connections, government leaders need those facilities to communicate with their response agencies and, in many cases, have the power to override the existing and operating systems.

Radio systems are not reliant on wires or electricity, and operators have the capability of establishing temporary antenna for receiving and transmission, he explained.

Bohach pointed out that the display system at their booth had the capability of going worldwide, using an antenna that measured about 24 inches tall, and was not even discernible above his shoulder.

In the aftermath following Hurricane ÔIniki, Bohach said a mobile-radio setup was established at the KauaÔi Fire DepartmentÕs Princeville fire station, so communication with officials in the Civil Defense office in LihuÔe could take place.

Alfred Darling, the director of the KauaÔi branch of the HawaiÔi chapter of the American Red Cross, is also a member of the Kauai Amateur Radio Club that numbers about 30 members spread out across the island.

Annually, Kauai Amateur Radio Club leaders host a Field Day competition where various setups are established, usually in a remote area, with members attempting to make contact with radio points worldwide.

This exercise demonstrates the capability of operators and equipment to function during times of disaster.

Goldsmith noted that, in 2005, the club did not host a field day exercise, but will be scheduling one for next year.