Veteran educators running for Kaua‘i’s BOE seat

Kaua‘i voters may have a tough time selecting Kaua‘i’s next representative on the state Board of Education in the Nov. 2 General Election.

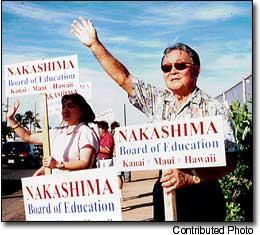

Both Dr. Mitsugi Nakashima and Maggie Cox are highly-respected educators statewide, and have top credentials.

Nakashima served on the DOE school board from 1988 to 2000 and as a DOE district superintendent of Kaua‘i schools. He has 50 years of educational experience under his belt.

Cox has 30 years of educational experience and, as a principal, opened King Kaumuali‘i School and Chiefess Kamakahelei Middle School, two of Kaua‘i’s newest and most innovative schools at one time.

Both candidates point to the Reinventing Education Act as a key tool to try to dramatically reshape Hawai‘i’s public school system. The legislation, also known as Act 51, was approved by the Legislature earlier this year.

But Nakashima said the measure must work in concert with state Department of Education’s “standards-based education program” to have real impact.

The program, in operation for about a decade, “specifies what all students should know and do and care about,” Nakashima said.

Cox said state legislators, educators, parents and students must join hands to work together for Act 51 to work. At the same time, Cox says it is too early to say what impact the education reform measure will have.

In addition to selecting the Kaua‘i representative to school board, the Kaua‘i electorate can select either Nadia Davies-Quintana or Herbert S. Watanabe to fill the Big Island seat on the school board.

Either Nakashima or Cox will be replacing Sherwood Hara, a longtime DOE board member who decided not to run to spend time with his wife and to travel.

The Reinventing Education Act is based on three principles:

- It empowers principals and residents with more authority and more decision-making power in the operation of schools. It allows individual schools more control over DOE funds. Principals, for instance, will wear two hats, that of fiscal managers and educator.

- It streamlines accessibility to resources.

- It requires teachers and DOE administrative staff to be held to “high, measurable standards.”

Nakashima said he supports Act 51, but stressed that “we need to sustain the effort to implement standards-based education,” which is geared to helping students learn how to “think on their feet” and prepare for future lives as adults.

“If you specify these standards and you teach toward them,” educators can measure how well students are learning, and make adjustments, Nakashima said.

Standards-based education was started in 1995, but the DOE didn’t make a major push for it until 1998, when a system was in place to implement the program, Nakashima said.

“I want to be able to carry out the curriculum and instructions,” he stressed.

“We are seeing some progress with standards-based education. We must continue on that course.”

The DOE board needs to lobby the legislature to continue to keep standards-based education viable, Nakashima said.

Act 51 is good, but it is not the main educational tool that will turn around Hawai‘i’s public school system, as some might believe, Nakashima said.

“Act 51 has more to do with other things than the ways school teach,” Nakashima said. “The act doesn’t get at the curriculum program,” which relates to teachers and their interaction with their students, he said.

For Act 51 to have any impact, the DOE board must work with Hawai‘i school Superintendent Patricia Hamamoto implement it, Nakashima said.

Nakashima pointed to the strengths of the measure, including the creation of a school community councils, which will work on financial and academic plans for individual schools.

The presence of the councils eliminates the need for independent school districts “because we will have people closest to the schools being involved in the schools,” Nakashima said.

One weakness of the act is that it doesn’t provide tutorial services for special needs students, those in the school system who may need the help most of all, Nakashima said.

Act 51 provisions call for the shifting construction and maintenance and repair responsibilities from the state Department of Accounting and General Services to the DOE.

Nakashima said while he believes schools are likely to profit from having more control over such matters, he wants to see how the shift in duties plays out.

On the surface, Act 51 also doesn’t mean schools will get more money from the Legislature, only possibly a redistribution of the same funds to individual schools that could improve school operations, Nakashima said.

The “weighted student formula” provision in Act 51 may bode well for schools, as the strategy provides funds not based on the school enrollment but based on individual student needs, Nakashima said.

The DOE is to provide more funds to educate students with special needs who require more resources.

Cox, meanwhile, believes Act 51 also will bring major changes to the DOE, and in order for it to work, all the “stockholders” in education – educators, legislators, parents and the community – should support it.

She supports the school community council concept, which envisions the creation of the councils at 22 schools statewide through a pilot project.

The councils will be established at Chiefess Kamakahelei Middle School, which Cox headed before retiring in recent years, and Kalaheo Elementary School.

The councils are designed to give “people more say” in education in Hawai‘i, Cox said, and she likes that.

The financial plan the councils will work on for individual schools will determine “how teachers are hired, what is going to be taught, do you need more or fewer teachers and resources,” Cox said.

Act 51 will put DOE board members in the field more often, requiring them to make more visits to the Neighbor Islands to find out what is happening in schools, Cox said, and she favors that new development.

From her point of view, more frequent visits to Neighbor Island schools by the DOE board weaken the argument for the creation of local school boards, Cox said.

“The (current) board member is doing what it is supposed to do,” but because residents live on a Neighbor Island, they feel they have less access to the centralized, O‘ahu-based DOE board, Cox said.

“Board members should meet informally with the community,” Cox said. “In reality, if the board members went out there, there would not be a call for local boards.”

Act 51 also is good because it calls for smaller teacher-student ratios from kindergarten to the second grade, and once the student count is exceeded for a classroom, more teachers will be hired, she said.

“There will be more money to hire teachers and more money train teachers,” she said.

Cox also supports a requirement of Act 51 to shift fiscal responsibilities and construction and maintenance programs from other state agencies to the DOE, giving school officials a more direct say in the operations of schools.

If Act 51 has a flaw , it would be the performance contracts for principals, a scenario in which principals could be fired if test grades at schools are not acceptable, Cox said.

“We already have a shortage of principals. We certainly can’t be firing principals, she said. ” Those are tough jobs. We have just added a bunch of stuff to their plates.”

Under Act 51, principals would go through more training to learn how to budget funds.

Cox said because Act 51 opens the possibility for major, positive changes in Hawai‘i’s education system, she wants to know as much as she can about it.

“I really want to know what is going on, and I have been meeting with principals and teachers to get their feedback (on Act 51),” Cox said.

Regardless of what Act 51 will do, the “instructions in the classroom make the difference,” she said.

On sweeping changes he would like to make in education, Nakashima said he wouldn’t want any, but stressed to need to “stay the course:” with standards-based education. Doing so will enable students to “reach academic proficiency,” he said.

The DOE’s standards- based program has requirements that every teacher should embrace – the need for more training, which would benefit students, Nakashima said.

On sweeping changes to improve public education in Hawai‘i, Cox said she would find some way to encourage the University of Hawaii to produce more locally-trained teachers.

Cox was recruited from the Mainland 30 years ago, and said she excelled in her career in Hawai‘i partly because she wanted to be here.

And while many Mainland-recruited teachers are qualified, some don’t stay because they become homesick, creating staffing problems for DOE, Cox said.

“We need more locally-trained teachers here, because they would be committed,” she said.

Cox also said there is a need to construct new facilitates to enhance learning.

Nakashima, who was a DOE school superintendent on Kaua‘i, said it was his impression school buildings and facilities on Kaua‘i are up to par. “We have been lucky that way,” he said.

Cox said the addition of programs and the planned development of a residential treatment facility for youths in Hanapepe will aid students and will benefit Kaua‘i’s school system.

Having more parental involvement is another way to improve education on Kaua‘i, she said.

On the issue of the recent announcement by DOE officials to cut daily salaries for substitute teachers from $119.80 to $112.53, effective Jan. 24, Nakashima said he didn’t know all the details about it. But on the surface, he felt the decision didn’t seem justified.

“The system looks for teachers who met the standards, and to cut their pay … substitute teachers won’t work in that capacity,” Cox said.

Cox said substitute teachers need and deserve a fair wage. Long-term substitute teachers, much like full-time teachers, draw up lesson plans and attend meetings and training, and so they deserve to have good pay.

The reduction complies with 1996 legislation that calculates the salary of substitute teachers to a salary schedule for public-school teachers, DOE officials said.

On the subject of what makes a good teacher, Nakashima said they must have solid technical skills and be able to reach out to students.

“There is a science and art to teaching,” he said. “The science part is that you know the subject, how to organize the lessons to teach the kids and make adjustments based on their needs. The art part is this. Good teachers follow up with students who aren’t doing well and support and encourage.”

Cox said, “teaching is a real talent. Some have it, some don’t. Teachers have to like it (their profession).”

“And training will allow for better teaching, and putting a twist that will make it better,” she said. “We have some wonderful teachers on this island.”

Nakashima can be reached at 332-8507 or at mitsnakashima@ earthlink.net. Cox can be reached at 652-3015 or at coxj024@hawaii.rr.com