Navy sonar exercises under fire over potential effects on whales

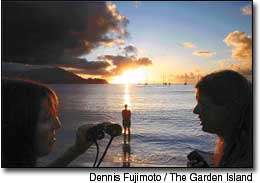

WASHINGTON — Residents of Hanalei Bay woke up Fourth of July weekend to a distressing sight: As many as 200 melon-headed whales, a small and sociable species that usually stays in deep waters, were swimming in a tight circle as close as 100 feet from the beach, showing clear signs of stress.

To keep the animals from beaching, the locals kept a vigil all day and through the night, until a flotilla of kayaks and outrigger canoes could be assembled to herd the animals back out to sea, in what was described as a “reverse-hukilau.” So far, only one young whale has been found dead.

But among increasingly worried whale advocates and researchers, the event set off immediate alarm bells: Melon-headed whales are not known to beach themselves, and nothing like this mass stranding close call has occurred in Hawai‘i for 150 years.

Attention quickly focused on the Navy and its use of active sonar — a wall of sound sent out to find underwater objects that can reach the decibel levels of a jet engine. Sonar has been implicated in several recent mass whale-strandings around the world, and the latest research has strengthened the association and suggested that the actual number of incidents may be far greater than anyone realized. The most recent study found that over the past 40 years, mass strandings of the most noise-sensitive whales off Japan occurred repeatedly in the waters near an American naval base, but were unknown in comparable areas elsewhere.

Several hours after the Hanalei Bay episode began, locals learned that a six-ship Navy fleet 20 miles out to sea had begun a sonar exercise the morning that the melon-headed whales headed toward shore. Officials at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration said it is too early to conclusively link sonar to the near-stranding, but they said their top priority is to learn more about the Navy exercise.

Navy officials, for their part, immediately ceased the sonar exercises in waters off the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Missile Range Facility at Barking Sands, near Kekaha, part of the biennial Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercises that continue through the end of this month.

A different kind of sea battle is brewing

Unless a different and convincing explanation can be found, the Hawai‘i incident is destined to become the newest case study in a high-stakes battle between environmentalists and the military over a technology that has been a staple of Navy operations for decades. Marine-mammal advocates say it has become increasingly apparent that sonar can lead to death for whales, porpoises and other sea creatures, and something must be done to limit its toll. But the military says that to protect the nation, it needs to use more sonar, not less. Navy spokesman Jon Yoshishige in Hawai‘i, a Kaua‘i native, said that the fleet does not believe that its sonar had anything to do with the unusual drive to shore of the melon-headed whales. He said that Navy records initially showed that sonar wasn’t turned on until about 8.30 a.m. on Saturday, July 3 — an hour after the first reports of whales in Hanalei Bay — but that a full investigation is now underway. He also said the fact that only melon-headed whales were affected suggests that sonar was not the cause, since sonar-induced strandings typically involve a number of species.

Joel Reynolds, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council, which sued the Navy over its plans for a new global sonar system, called the Navy response “consistent with what we’ve seen in previous instances of strandings close to naval sonar activity — they say ‘We had nothing to do with it.’ Hopefully, a real investigation will determine if that’s true or not.” The latest incident could hardly have come at a worse time for the military. A series of congressionally mandated conferences has been underway for months, under the auspices of the Marine Mammal Commission, to assess the effects of sonar and other underwater noise on whales, porpoises and dolphins, and the group is expected to make recommendations to NOAA and Congress next year.

Shallow-water range planned in Atlantic

In addition, this fall Navy leaders intend to unveil plans for a first-ever underwater sonar testing range. The so-far unpublicized proposal would establish a 10-to-20-square-mile range in the shallow waters off the Carolinas for sophisticated and intensive sonar training. Navy officials say they need the range to train sailors in detecting a new generation of inexpensive and “quiet” diesel submarines that several nations have acquired and that could be deployed to threaten the coastline.

The Navy leaders, working with information and advice from NOAA officials, are just finishing an environmental impact assessment for the testing range. Details of the plan and its possible implications for sea creatures remain sketchy, but the waters off the Carolinas are known to be on the migratory routes of several species of whales. Military leaders have already been forced by a federal judge to limit deployment of a different sonar project — a $350-million, cutting-edge, low-frequency sonar system it wants to deploy worldwide. The judge concluded last year that government officials had not properly considered environmental effects before allowing Navy crews to use the new sonar.

That led to an agreement between Navy officials and leaders of environmental groups to limit the sonar to a section of the Pacific Ocean off east Asia, but Navy lawyers have appealed several aspects of the decision. With these major new projects underway, Navy leaders suddenly have to deal with a problem involving old-but-still-evolving technology that, until recently, was not seen as an environmental threat. Only after the stranding of 17 whales in the Bahamas during a sonar exercise in 2000 did the Navy acknowledge — a year later — that its traditional, mid-frequency sonar could be lethal to marine mammals. In 2002, a joint Spanish-American naval exercise off the Canary Islands had to be stopped after it, too, touched off the stranding and deaths of beaked whales, a deep-diving and generally reclusive animal.

With interest and research growing, new reports strongly suggest that traditional sonar has caused many more mass strandings than previously believed. A database of known beaked-whale strandings and naval maneuvers put together by James Mead of the Smithsonian Institution marine-mammal program has found an overlap of “between 100 and 200 cases” in the past four decades. He said the overlap doesn’t prove sonar caused the strandings, but “the association certainly is quite impressive.”

Federal report links sonar, beachings

Just this month, Robert Brownell of NOAA in California presented a paper at the International Whaling Commission that examined beaked-whale strandings since 1960 near an American naval base in Japan. He found evidence of at least 10 mass strandings — involving between two and 13 animals — in the waters near the American naval base at Yokosuka. For comparison, Brownell examined records for the coast of New Zealand and other areas off Japan and found no indication of mass strandings in either locale.

“The co-occurrence of the mass strandings and the U.S. Navy activity in this region strongly suggests” a relationship, Brownell concluded. Although the Navy has used “active” sonar — where ships send out sound to bounce off underwater objects — since World War II, the power of that mid-frequency sonar has increased over the years. The apparent link between this type of sonar and major whale strandings is a relatively new discovery, and it has put Navy leaders on the defensive. Several hours into the recent Hanalei incident, NOAA officials asked the Navy to stop its sonar exercise — which included two American and four Japanese ships — and the commanders complied. Navy officials say the service is the primary environmental steward of the world’s oceans, funding 70 percent of marine-mammal research in the United States and almost 50 percent worldwide. Officials also say that the number of sonar-related incidents is small, though worrisome. Rear Admiral Steven Tomaszeski, the Navy’s chief oceanographer and for 30 years a Navy combat officer, said the seamen involved in the Bahamas stranding in 2000, for instance, “told us they felt really terrible about what happened to the whales. But the truth is we just didn’t properly consider that they might be there.

Not much is known about whale hearing

“We actually know more about the surface of the moon than we know about our oceans,” he continued. “We don’t really know where many of the whales are, and we don’t know too much about how a whale’s ear works. Some would say that if you don’t know, then don’t take chances and let’s keep our acoustic energy out of the water,” he added. “It’s the precautionary principle. But in good conscience, I couldn’t send a fleet out to sea without sonar. It’s the best anti-submarine defense by far.” To be effective, however, the sonar systems need trained sonar operators, and Tomaszeski said that requires on-the-water experience. Training maneuvers occur regularly around the world, he said, and it was a sonar-training exercise that brought the Navy into contact with whales in the Bahamas in 2000, the Canary Islands in 2002, and apparently off Kaua‘i this month.

Whale advocates and environmentalists say they fully understand that sonar has to be used without restraint in times of war. It’s the training exercises, they say, that are needlessly harmful.

Environmentalists familiar with the plan for a shallow-water, sonar-testing range say Navy officials should expect opposition to the proposal. According to Donald Schregardus, deputy assistant secretary of the Navy for the environment, planning began about four years ago. He said Navy leaders want to install underwater microphones and sensors to create a facility where sailors can better train to use sonar.

He said Navy leaders are working with federal environmental officials to study which animals inhabit or migrate through the area and at what times and densities, and to assess the likelihood of disturbing marine mammals. “We want to improve underwater training and detection,” Schregardus said. “And we want to take that knowledge and information and establish a range on the West Coast, too.”

The Garden Island contributed to this report.