Perpetuating the cultures of Hawaii and Micronesia is the goal of a group of Native Hawaiians and expert canoe builders from Micronesia who together have built on Kauai a hand-made koa wood canoe. The 16-foot-long handsome hardwood canoe was recently

Perpetuating the cultures of Hawaii and Micronesia is the goal of a group of Native Hawaiians and expert canoe builders from Micronesia who together have built on Kauai a hand-made koa wood canoe.

The 16-foot-long handsome hardwood canoe was recently launched at Hanalei Bay.

It may be the first hand-made koa outrigger canoe built on Kauai in nearly 200 years, and is believed to be the first since the death of King Kaumualii in 1824.

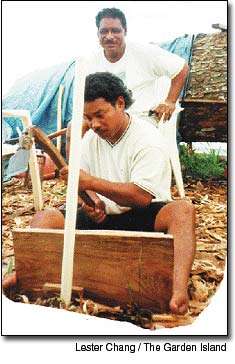

The canoe was carved and hewn with handmade adzes tools, implements that are more tied to ancient times than to modern times, and still used in Micronesia, where lawn mower blades have replaced the basalt blades once used.

The making of the canoe could mark the return of building canoes in the traditional Polynesian way, without power tools, the builders said.

“This is awesome,” said Robert Pa of Hanalei, who was invited to help build the canoe. “The idea is to show people what we have done here. If people want, we can teach them how to make one, navigate it using the stars.”

The boat was launched on May 24 following a blessing by Donna Keale. She is the daughter of the late Moses Keale, a longtime Hawaiian community leader and a retired board member of the state Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

Also attending the gathering was Keale’s husband, Santos Wichimai, an expert canoe builder, a former vice House speaker for the Yap Legislature in the Federal States of Micronesia and now a resident of Anahola.

The ceremony was attended by canoe builders now on Kauai from the island of Ifilik, an atoll in the Federated States of Micronesia. They are Lucas Hiemai, a master carver with 20 years of experience, and his helpers, Xavier Tachiyelimal and Timothy Igemai. Each man has ten years of canoe-building experience.

Also attending was Peter Narburgh, a Kilauea resident who has lived on the island of Ulithi, an atoll in the Federal States of Micronesia, and a co-sponsor of the project. Pa and his family also attended the ceremony.

The koa canoe was built on Narburgh’s property over the last four months, and is designed for paddling in lagoons. Plans call for the craft to be used for fishing in Hanalei Bay and elsewhere.

The idea for the project came from Wichimai, who missed his home island of Ifilik, and wanted to share his culture with Kauaians.

After Wichimai consulted with the chief of Ifilik island, the three Micronesians came to Kauai in January for the canoe project.

The Micronesians and others initially found what they thought was a good candidate for the canoe, a Philippine mahogany log found on the Ahukini coastline makai of the Lihue Airport runways.

But that log was deemed unusable, and with Pa’s help and approval by the state Department of Land and Natural Resources, the men located a fallen 20-foot-long koa log in an area of Kokee known as “Pele’s heiau.”

From under a makeshift tent made from hau bush and palm fronds on Narburgh’s property, the Micronesians began making a large voyaging canoe.

But their plans changed after the builders determined that a part of the log had been bruised while it sat on the ground in Kokee. They shifted gears and decided to build the smaller paddling and fishing canoe.

Paddling canoes are generally less than 20 feet long and deep-water, ocean-voyaging canoes range from 25 to 65 feet.

To make the canoe, the Micronesians fashioned handles from strong branches to make adzes of varying sizes.

With the help of Narburgh, the men formed numerous adze blades from lawnmower blades, shredders and pipes that were used for gouging and finishing work.

The Micronesians knew about power tools, but opted not to use them to show instead the traditional way of making Polynesian canoes, Wichimai said.

“Hand-built is better, because you are putting your mana (supernatural or divine power), your sweat and your time into making one piece of art,” Pa said.

Pa said koa canoes made in Hawaii with power tools can fetch a price of up to $30,000, but felt the one that he and others have worked on Kauai was “priceless” because of its uniqueness.

The Micronesians used the length of fingers, hands, arms, feet and legs or the spine of palm fronds to make the canoe, to be in line with ancient Polynesian canoe-making practices, Wichimai said.

Because of the way the canoes are made, each one actually represents the physical characteristics of the builders, he said.

Wichimai said he learned canoe making from his father, and worked on his first canoe with others by the time he was ten years old. By the time he was 19 years of age, after learning all phases of canoe building from his father, he was declared a master canoe builder.

Armed with adzes and working cooperatively, the Micronesians and Uncle Vince Napolis, a resident of Hanalei and others generally worked six days a week, taking off only Sunday.

They removed the bark of the log and used wide-blade adzes to gouge large chunks of wood from the log as they began shaping the canoe.

They continuously worked on the bottom and top side of the log so that the canoe would be balanced. The builders then used adzes with smaller blades to gouge out the interior of the log, making sure the width of the hull would be uniformly one inch thick from the lip of the hull to the bottom section of the hull.

The log that was used for the canoe had become weak because of the way the log sat on the ground in Koke’e.

To make the hull stronger, the builders replaced a section of it with a new koa plank.

The builders used glue and a “gasket” made from flattened coconut husk in inserting the new piece into the hull. The builders braced the work with monofilament wire.

They made two prows that were identical in size and were put on the back and front of the boat. With the prows, one can line up the stars for navigational purposes.

Using strong string that was made from coconut husks, the builders made lashings that were used to help hold the craft together and to create an ama that was attached to the canoe.

The canoe boasts a v-shaped keel that allows the craft to tack well into the wind.

Back on their island, the Micronesians use either mahogany and breadfruit trees to build their canoes, but favor breadfruit trees because they are lighter and stronger.

The Micronesians observed kapu or taboos in building the canoe. For instance, they could not interact with women during the building, Wichimai said.

“They consider the ocean a woman, and she is very jealous if she smells another woman on board,” he said. “The ocean will be rough because the ocean is jealous.”

Narburgh said the canoe is a life and death matter to Micronesians. “They go out in the ocean and, if there is anything spiritually wrong with the canoe, it could cost them their lives,” he said.

When canoes were built on Ifilik hundreds of years ago, the master canoe builder visited the canoe under construction as his first task of the day, Wichimai said.

The canoe master blessed the canoe daily and “asked for hands and food for the helpers,” Wichimai said. The canoe master also swept away the work of any sorcerers who cast a spell over a canoe.

Thousands of years ago on Ifilik, canoe builders used shells and stones to make canoes. As a way to expedite the making of a canoe, canoe builders set parts of logs on fire, to gouge out wood before the shaping of canoes, Wichimai said.

The art of canoe making on Ifilik, and it was probably pretty much the case elsewhere in Micronesia, changed dramatically in the 1800s when Spanish galleons visited the island, and islanders saw sailors with an ax.

As an Ifilik story goes, a boy took the ax, and despite whippings by the ship captain, he, at the urging of his father, kept the ax, Wichimai said. It was in much demand on the island.

Other Ifilik islanders coveted the ax and gave the boy’s family fruits, coconuts and food in exchange for the temporary use of the ax to make canoes, Wichimai said.

In the 19th century, people on Ifilik found metal blades were available on Saipan and sailed there to acquire them to make their own adzes. Wichimai said.

Canoe builders who lived on Ifilik in ancient times were not held in higher esteem than any other member of their society back then, Narburgh said.

The canoe builders serve a function, much as farmers, fishermen or coconut climbers had done, in a society that stressed cooperation in order for people to survive in austere and isolated conditions, Narburgh said.

Several hundred people who populate the island live without electricity, motor boats or many electrical appliances, although people can buy radios and batteries. Yap government ships make periodic visits to drop off supplies.

In place of electronic devices like televisions or computers, people sing and dance, and they prefer this way of life, Wichimai.

While three Micronesians said they like the modern conveniences found on Kauai, they yearn to be back home for the upcoming aku fishing season, Wichimai said. They bring back fish that help the community on the island, he said.

The Micronesians and others approached the launching of the Kauai canoe with happiness and a sense of completing a special project.

The lei-draped canoe was transported down to Hanalei Bay by a truck and trailer provided by Haena resident Tommy Taylor.

The Micronesians, however, plan to return to Kauai one day, to start work on a second canoe that all hope will raise the consciousness of their culture and that of Hawaiians, Wichimai. Rachael Pa, Robert Pa’s 9 1/2 year-old daughter, thought the first project was special and looked forward to the next one. “I want to help with that one,” she said. “I think it is something I will remember all my life.”