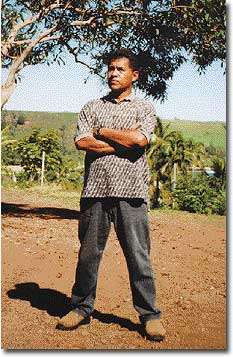

When 50-year-old Honolulu resident Herb Silva came to Kaua’i three weeks to live, he knew the rest of his life was going to have meaning. Not only was Silva going to leave Honolulu’s fast-paced life style for Kaua’i’s slow-paced lifestyle

When 50-year-old Honolulu resident Herb Silva came to Kaua’i three weeks to live, he knew the rest of his life was going to have meaning.

Not only was Silva going to leave Honolulu’s fast-paced life style for Kaua’i’s slow-paced lifestyle and relax in Moloa’a Beach where he owns property, he was going to reconnect with his family and the Hawaiian culture.

On Kaua’i, Silva said he is going to help guide the use of properties in Moloa’a Valley and Bay that have been in his family since 1853.

Also, Silva, who is part Hawaiian, said he plans to restore an ancient road used by Hawaiian royalty, an underground spring and stream and a pool at the beach.

The proposed work sits on land Silva says he can use through family land documents.

Silva said he researched his future project at the Bishop Museum on O’ahu over the past two years before he decided to take on the challenge.

Through his work, he wants to perpetuate the Hawaiian culture and to bring greater public awareness, especially among Hawaiians, about the history of ancient Hawaiians in Moloa’a.

“I want people to know what Hawaiians did here,” Silva said. “I also want to preserve my ancient kuleana rights, which includes the trail and protection of the eco-system.”

For his work, he has proposed to set up the “Ke Awawa Community Development Center” on lands he owns on the northwestern rim of Moloa’a Bay.

Silva foresees the day when the non-profit group will set up partnership programs with the University of Hawaii.

It is his hope, he said, the center will become a repository of information about the history of ancient Hawaiians in Moloa’a and that UH students can come to the area for their studies.

“I eventually want to get approval from the state, landowners and the community for my restoration work,” Silva said.

The restoration project is already picking up steam, he said, as he wants to cut a trench next to the stream to prevent mud and debris from flowing into the waterway.

His future goal is to clear the stream and make it free-flowing again.

For over 30 years, the Boiser Family of Moloa’a, maintained the stream. But the work tapered over in recent years because the amount of work was overwhelming and relentless, Silva said.

“The spring is still functioning, but no one has taken care of the hydrology of it,” Silva said. “It is a trickle now, but it was a full-blow stream before. And it will be again when I am finished with it.”

The mountainside stream sent water into an ancient pool located just above the beach, Silva said.

The pool was covered with backfill in the 1950s for reasons unknown, Silva said. “But the walls remain and it needs to be dug up.”

The freshwater pool provided a place for relaxation and a source of food – shrimp – for ancient Hawaiians, Silva said.

“It was a special thing for Hawaiians to have this. It was a like a living thing for them, because there was water, which is life,” Silva said.

The ancient road that runs along the pool and stream also ran along the coastline of Moloa’a Bay.

Areas mauka of the beach was the site of ancient fishing village. The area also was a playground for the royalty from the time of “King Kamehameha I to King Kamehameha V,” Silva said.

And according to Silva, his great, great grandfather, Kuhaulua , was considered a konohiki (like a land manager) for the area and on O’ahu.

A year ago, Silva said he laid out what he planned to do in Moloa’a to the University of Hawai’i’s Center for Hawaiian Studies.

“I was asked to provide more information about my plans, and that is one reason why I am spending more time here, the reason I moved back,” Silva said.

Silva was born and raised on O’ahu, but lived on various islands in Hawai’i. In his lifetime, he ran a tour business on O’ahu, worked for 10 to 15 years as a computer programmer and analyst, worked as a carpenter and, most recently, got involved with paralegal work.

He traveled to Kaua’i many times to visit family in the past, and, because he wanted to get away from the “rat race of Honolulu,” he began planing his move to Kaua’i five years ago.

As a younger man, Silva said didn’t realize the value of the land in Moloa’a that had been guarded by his ancestors.

Silva said his grandmother, Uika, held and protected land documents and later entrusted them to her daughter-in-law, Barbara Silva, his mother.

“If not for them, I would not have this land and the chance to do what I want to do on Kaua’i.” Silva said. “I am grateful to them.”

Staff writer Lester Chang can be reached at 245-3681 (ext. 225) and mailto:lchang@pulitzer.net