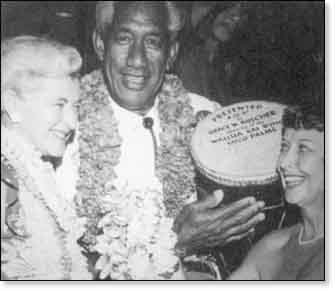

The legendary Duke Kahanamoku spread his aloha to Kaua’i in various ways. He planted a coconut tree along the walk of fame at the Coco Palms Resort, and visited the Kauai Resort in the days when Kaua’i waterman Percy Kinimaka

The legendary Duke Kahanamoku spread his aloha to Kaua’i in various ways. He planted a coconut tree along the walk of fame at the Coco Palms Resort, and visited the Kauai Resort in the days when Kaua’i waterman Percy Kinimaka was the beach captain at the hotel set along Kalapaki Bay.

A little known act of kindness by Kahanamoku provided a Waikiki-style redwood surfboard in 1935 for 12-year-old Kaua’i surfer Hobey Wichman. Wichman is best known as Hobey Goodale; his surname was changed later in his life in honor of his late father.

Kahanamoku was sympathetic to the plight of the Kaua’i surfers at Kalapaki who had no top of the line surfboards at the time. Goodale’s grandfather, Kaua’i legislator and community leader Charles Rice, had brought the situation to the Duke’s attention. Rice’s home at Kalapaki was then located where the Marriott Resort is today. The beach front home was given to Rice as a wedding present, and Goodale frequently stayed at the home, traveling down from his family’s home up in Wailua Homesteads to attend Lihue School. The visits opened up the world of surfing for him.

In a typed letter, hand-signed by Duke Kahanamoku on his Office of the Sheriff of Honolulu letterhead, the famous surfer and Olympic swimmer let the young Kalapaki surfer know his board was in the works, and provided advice on advancing as a surfer.

Kahanamoku wrote: “Surfing is a sport equal to none in this world. It is in a class by itself and if one starts as young as you have, it will make you a healthy and clean young man and the exercise you get out of it will come in handy in your later life. I owe my swimming strength to surfing and from what your grandpa tells me, you are quite an expert.”

The redwood board arrived at Nawiliwili as freight aboard an inter-island steamer and was shaped by Waikiki beachboy Peter Makia, along with some guidance from the Duke.

“It was about eight feet long, maybe 10 feet, it wasn’t huge, but it was four inches thick at the back,” Goodale said in an interview with The Garden Island. “It had a varnished finish and no fin.”

“We knew him (Duke Kahanamoku) as an idol, and when it arrived everybody wanted to try my board,” he said.

Goodale continued to surf the Duke-inspired redwood board at Kalapaki through the war years of 1941-45, until he joined the Army and left Kaua’i, never to ride his treasured board again.

“This board was lost in the tidal wave in 1946,” Goodale said.

Goodale affectionately recalls the uncrowded surfing days at Kalapaki in the 1930s, years when he rode the surf in all wave and weather conditions.

“We would use what they call today the body board, we’d get the ends of 1×12 lumber to ride on, or just plain bodysurf,” he said.

When he was eight or nine years old Goodale’s grandfather brought over three surfboards from Waikiki for use by his grandson and friends.

“Nobody was surfing on Kaua’i, that didn’t come until way after the war, and there hadn’t been any surfing for years,” Goodale said. “There was only surfing at Kalapaki, this was during the Depression, five guys would be a crowd, there were no cars for us to go anywhere else. You didn’t get in a car flying around, we didn’t have a lot of money to go to the movies – this was in the middle of the Depression, so we made our own fun down on the beach. We did a lot of diving and spearing for fish too.”

“We only had the three boards; one was a little one, one a blue one that ended up with a big crack,” he said. The wooden surfboards had no fins and weren’t very maneuverable and ridden pretty much in a straight line, “allowing more than one guy to take off at a time.

Among his surfing friends who rode the break at Kalapaki were Goro Sadaoka and Takugi Fujimura, the son of a photographer who lived in a house opposite where the entrance to the Marriott Resort is today.

John Makanani, Henry Panui, John Ah You and Bill Paia were other Kalapaki surfers in the 1930s, Goodale recalled.

“Bill Paia was from Honolulu and knew how to surf, he told us the etiquette of surfing – don’t’ run over the other guy ,” he said. “Some of the surfers were older than me, but most were about the same age. Some surfed on a part-time basis, and some were from Lihu’e, though mostly they were from Nawiliwili. Nawiliwili was a lot more of a community in those days.”

“We went over the falls numerous times and had to swim, but we were all like fish in those days,” Goodale said. “My parents encouraged me to surf, they thought it kept me out of trouble. Like the Duke said, it was a nice clean sport. There was no smoking, well not much…and no drug culture among surfers in those days.”

One of Duke Kahanamoku’s brother came through with some surfing advice for Goodale and his friends. “One day Doris Duke was on Kaua’i with Sam Kahanamoku. He saw what we were doing, showed us how to do it right.

Goodale said though he surfed the same waves that breaks at Kalapaki today, the way surfers rode waves was quite different in the 1930s.

“We had no fins (for bodysurfing and diving), the regular surfboards had no tethers so we had to swim,” he said. “You used your foot for the rudder, lean on one side or another, to turn right you put a lot of weight on right side of the board,” Goodale said. “I only got wacked when I was bodysurfing, by someone else who was using my board; I got four stitches in my eyelid.”

Goodale said he enjoyed surfing at Kalapaki in all surf conditions.

“I was a wild one because there was no wave I wouldn’t catch; I’d go out on any day,” he said. “One day I got up early in the morning, it was getting close to summer and the waves were breaking right across the bay practically. I went out. My grandmother waved a towel (to signal breakfast was ready), and I came in. Later I went back out all day until she waves the towel again for lunch.”

There were also some scary times on the break off Kalapaki Bay.

“One day we’re all sitting out there on our boards, I was surfing with two Hawaiian boys, one was Raymond Ellis,” Goodale said. “We’re sitting out there waiting for a wave and saw a shark fin go between John Makanani and myself. The two Hawaiian boys paddled in and I waited for a wave. One of their mothers said ‘don’t ever fool with Hobey in the water because the shark is his aumakua and he’ll get you!'”

When he turned 13, Goodale traveled across the Kaua’i Channel to attend Iolani School in Honolulu, coming back to Kalapaki for stays at his grandparents’ home during Christmas and Easter holidays.

The attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941 halted Goodale’s education, and he came back home to work with his grandfather on his family’s ranch at Kipu. This also allowed him to again surf Kalapaki on a regular basis.

“I’d work on the ranch, come back to surf a couple hours, sometimes I ate hamburgers at the pool hall at Nawiliwili,” he said. “I worked on the ranch until early 1945, and then went into the Army. The surfboard was lost in a tidal wave when I was up in the Aleutians. It was at my grandfather’s place and disappeared. The last time I surfed was in 1953. Richard Sakoda, a former Kaua’i policeman, got a hollow board about 12-15 feet long, made out of plywood and hollow in the center, and that was the last board I ever rode. He kept it hidden in the trees at Kalapaki…my children thought it was quite something for me to surf.”

The world of surfing at Kalapaki in the 1930s and 1940s is now history, while the break continues to be a popular spot for Kaua’i surfers and one that is connected to the heritage of Duke Kahanamoku.

Most of the old time surfers are now gone.

“Of all the guys I surfed with I don’t think there are any left alive except for me and Richard Sakoda,” Goodale said.