WAIMEA – The reporter continues to rack his brain to come up with the name of the educated chap who told him it was easy to farm taro, just plant and watch it grow, and why the reporter was silly

WAIMEA – The reporter continues to rack his brain to come up with the name of the educated chap who told him it was easy to farm taro, just plant and watch it grow, and why the reporter was silly enough to take that as gospel truth.

The reporter knew from talking to Hanalei Valley farmers that getting the next generation to take over the fields was a tough sell, because the younger folks understand how physically demanding the work is.

Another perplexing situation developed during a long-anticipated road trip to visit taro farmers in Waimea, where the farmers should be surrounded by supportive neighbors anxious to see a young family succeed working the land.

Instead of allowing Waimea Valley water to flow naturally across Ray Ard and Ellyson Ard-Manus’ 9.5 acres of land leased from Robinson Family Partners as it had for generations, one relative turned off the flow.

The Ards solved that problem by finding spring-fed, flowing water where all the neighbors, and even the Robinson family, told them none existed. Or, if any existed, it was brackish (a mix of saltwater from the sea and fresh water from other sources).

“We just prayed and dug and there was the water,” said Ray Ard, 36, whose farm now sees more flow than the nearby Menehune Ditch, and supplies water flowing from the farm down a ditch system into the Waimea River a few hundred yards before it reaches the ocean.

The struggle to become and stay taro farmers when all around them said it couldn’t be done on the place they’re doing it, makes the Ards’ story one worth telling.

Blessed with incredible drive, determination, a taste for hard work, their faith, each other, her 10-year-old son and not much else, they worked the better part of two years to convince the Robinson family they had what it takes to return to taro the area just off Menehune Road.

It had produced taro, sugar and corn before the Ards saw the field of trees and scrub bushes and envisioned taro once again, and Ray Ard knew the lowest section of the valley in the shadow of the wettest spot on earth must contain some water.

Ironically, the financial institution that did say “yes” to them wasn’t a traditional bank, which wouldn’t take a chance on a young couple without much farming or positive credit experience.

The personal touch of Larry Dressler and Kaua’i Micro, a lender of small amounts to small businesses traditional banks won’t normally lend to, helped the Ards reach the point where they are almost ready to get some traditional financing, and work the farm so that it provides a sustained, family-sized income.

“They went out on a limb for us,” said Ard-Manus, 30.

The enterprise financing Dressler and Kaua’i Micro provide offer him “the ability to give somebody a chance,” said Dressler, a former business banker with Bank of Hawai’i.

Along the way, Kaua’i Micro has made several loans to the Ard family, convinced that with their hard work and the perpetual demand for taro (used primarily to make poi), the farm will be a success.

The family will soon also be the first to enjoy a loan through Kaua’i Micro’s new agricultural lending program, formed after a statewide study revealed that there were no micro-lenders in Hawai’i in the business of loaning small amounts of money to small farmers.

Kaua’i Micro is the first.

A look at the farm tells you that from a production standpoint, this could be the breakout year. Currently harvesting around 40 bags of taro a month, the farm is poised to do twice that in full production.

The only west side farm harvesting on a weekly basis, the Ards’ operation sends nearly all of its product off-island, and has willing buyers on O’ahu, and Aloha Poi on Maui.

They have 19 fields in various phases of production, four more dug and room for four more, and by May or June expect to begin harvesting two fields a month, while shortly after that planning to plant three fields a month.

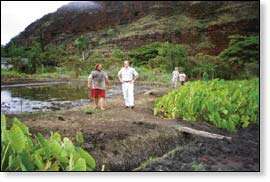

The couple, working seven long days a week and working alone, do all the field preparation, planting, weeding, fertilizing, harvesting, packing and trucking. By hand. Ray Ard says the toughest part of the work is preparing a field for planting, as the ground beneath the mud is hard-packed clay and soft dirt and sand that got as hard as concrete over the years of corn and sugar production on the land.

Once that hard-pack is broken up and gets some water on it, it becomes mud again. But getting it up from the depths of 12 inches or more underground to the surface is tough work. Almost unbelievably, most of the work the family has done to get to the end product of 19 taro-producing patches has been done by hand.

Ard the day of the reporter’s visit last week was toiling away with the pick ax, preparing a field that his wife would plant as soon as he was done.

Small fish in the fields eat mosquitoes before they develop into flying menaces, and the kind of snails these fields have eat dead taro leaves, not the live plant, so are kept around for the good work they do, he said.

After September 11th, when things in the world turned ugly or just plain upside down, the main source of family income dried up, as the poi company on O’ahu fell nearly three months behind on payments for the Ard family’s crop.

That meant the family had to delay payments to its creditors, use credit cards to get fertilizer and other necessary farm goods, and continue to hand-till and hand-work the fields.

“We never thought about quitting this,” said Ard, who credits Kazuo Iwatate of Makaweli, a retired Robinson family employee, for teaching him just about everything he knows about taro.

For more information about Kaua’i Micro, please call 632-2004.

Business Editor Paul C. Curtis can be reached at mailto:pcurtis@pulitzer.net or 245-3681 (ext. 224).